Constitution-Making in Pakistan during the 1950s: Causes of Delay

Abstract

Constitution-making in Pakistan has unfortunately a chequered history. After gaining independence in 1947, Pakistan adopted the 1935 Indian Constitution with slight modifications as an interim constitution and started earnestly to frame a consensus document to serve as its permanent constitution. However, due to peculiar circumstances, the complexity of the issues involved, and the incompetency of the political elite, it took them more than seven years to accomplish the task.

This essay is an attempt to discuss this issue in detail and pinpoint the reasons for the extraordinary time taken to frame the Constitution during the 1950s.

Introduction

After its independence from Britain in 1947, Pakistan adopted the 1935 Indian Constitution with slight modifications as an interim constitution. Known as the Pakistan (Provisional Constitutional) Order 1947, it established the federation of Pakistan, comprising East Bengal, West Punjab, Sindh, the NWFP, Baluchistan, and any other area that might accede to Pakistan. This Interim Constitution provided for a strong central government, a governor-general with non-renewable powers, and very limited representation.

At the same time, the National Assembly, which also worked as the Constituent Assembly, started working on framing a new constitution. Its subcommittee, the Basic Principles Committee (BPC), submitted the Objectives Resolution, which contained guidelines for framing the Constitution. The Objectives Resolution, reflecting the views of the strong religious groups in the country, was approved by the Constituent Assembly on March 12, 1948. However, afterwards, it was an uphill task to frame the Constitution, which got derailed off and on for one reason or another for the next seven years.

The Committee, headed by Liaquat Ali Khan, submitted its first report on September 28, 1950, which was not approved mainly because it gave equal representation to both wings, although the East wing had more population than the West and Urdu was the state language. After his assassination on October 16, 1951, the Second draft was presented on December 22, 1952, by Khawaja Nazim ud Din. It proposed bicameral legislation, for the lower and upper houses to have equal representation (upper house, 60 each, and lower house, 200 each). This also came under criticism because of the equal seats for both wings and Urdu as the state language.

The third draft was presented on October 5, 1953, by Muhammad Ali Bogra. Known as the Bogra Formula, it compromised on disparity and proposed bicameral legislation with a lower house of 300 seats elected on a population basis (East Bengal 165, remaining 4 units of West Pakistan 135). It also proposed an Upper house of 52 seats, 10 each for each of the five constituent units, and 2 reserved for women.

However, two political developments changed the whole complexion of the political landscape, and consequently, the framing of the Constitution took a back seat.

- First, the Muslim League was completely routed by a hotchpotch coalition of political parties in the provincial elections held in the East Wing in March 1954. The new government was dismissed soon after the assumption of power in East Pakistan

- Second, the National Assembly passed a bill in September 1954 that made the Governor General (GG) act on the advice of the PM. It was also made mandatory for GG to appoint a Prime Minister who is not only a member of the assembly but also enjoys the confidence of the majority.

Seeing the erosion of his authority, Governor-General Ghulam Muhammad dissolved the Assembly on October 24, 1954. The Supreme Court, headed by Justice Muhammad Munir, upheld the decision under the law of necessity.

After abolishing the provinces in the West wing and converting them into One Unit, new Elections were held on June 21, 1955, to elect 40 members each from both wings. The newly-elected Prime Minister Chaudhry Muhammad Ali took on the task of constitution-making and constituted a special committee for this purpose. The committee presented the draft Bill to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on January 9, 1956.

The bill was opposed by Bengali leaders. Maulana Bhashani, the leader of the Awami League in East Pakistan, even threatened secession to press for autonomy. Later, his party staged a walkout from the Assembly on February 29, when the Assembly adopted the Constitution, and boycotted the official ceremonies celebrating the inauguration of the Constitution.

However, despite their opposition, the Constitution, mainly based on the Government of India Act 1935, was enforced on March 23, 1956. It was unicameral legislation to be elected based on parity between the two provinces. With this, Pakistan’s status as a dominion ended, and the country was declared the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Constituent Assembly became the interim National Assembly and Governor-General Iskandar Mirza was sworn in as the first President of Pakistan

Reasons for Delay in Constitution-Making in Pakistan

The process of constitution-making in Pakistan faced significant delays due to a multitude of intertwined factors that reflected the complex political, social, and religious landscape of the newly formed state. This article elaborates on the key reasons contributing to these delays.

A. Post-War Political Circumstances

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the political landscape in the Indian subcontinent underwent significant changes that influenced the urgency surrounding the dissolution of the British Indian Empire. The leadership of the Muslim League, while initially advocating for a separate homeland through the Lahore Resolution of 1940, became increasingly pessimistic about achieving immediate independence. Despite their hopes for constitutional guarantees for Muslims in a united India, the realization of partition became imminent, leaving little time for the essential task of constitution-making. The focus shifted towards negotiating the partition rather than laying the groundwork for a new constitution.

B. Nature of Pakistan’s State

Pakistan emerged as an independent nation-state on August 14, 1947, as a result of the partition of British India. However, the peculiar geographical configuration of the country posed unique challenges. The nation was divided into two wings — East and West Pakistan — separated by approximately 1,000 miles of hostile territory. East Pakistan had a larger population and better literacy rates, but it lacked representation in key governance institutions. Conversely, West Pakistan, although more developed in terms of infrastructure and military presence, faced significant administrative challenges. This imbalance of power and representation created difficulties in reaching a consensus on various constitutional issues, complicating the process of establishing a unified governance framework.

C. Complexity of Issues

The process of constitution-making was further complicated by the numerous and complex issues that needed to be addressed. Some of the most contentious issues included:

- Form of State: The political elite from West Pakistan favoured a unitary state with a unicameral legislature, whereas their counterparts from East Pakistan sought a federal structure with a bicameral legislature and maximum provincial autonomy.

- Form of Government: Similarly, there was disagreement over the type of government; West Pakistani politicians advocated for a presidential system, while those from the East pushed for a parliamentary democracy.

- Representation Formula: East Pakistan demanded greater representation in the legislature based on its population, while West Pakistan sought parity between the two regions, leading to tensions over equitable representation.

- Role of Religion: Although declaring Islam as the state religion was not contentious, defining the role of Islam within the constitution sparked heated debates that divided the nation.

- Language Issue: The language question became another flashpoint, with demands for Urdu as the sole national language conflicting with calls for recognition of regional languages, particularly Bengali. This dispute extended beyond constitutional matters, causing political and economic friction between the two wings of the country.

Other significant issues included the protection of minority rights, the economic system (capitalism versus socialism), and international relations, all of which further complicated the constitution-making process.

D. Condition of Statecraft

Unlike India, which inherited a fully functioning administrative apparatus, Pakistan faced the daunting challenge of building its governance structures from scratch. A mass exodus of administrative talent, financial resources, and entrepreneurial expertise occurred during partition, leaving the new state with a severe shortage of qualified personnel to run government offices and manage public services. Additionally, communal riots during the partition resulted in a refugee crisis, overwhelming an already struggling state. These challenges diverted attention and resources away from constitution-making, as the government focused on immediate concerns such as maintaining stability and ensuring territorial integrity.

E. Constituent Assembly’s Ineffectiveness

The effectiveness of the Constituent Assembly was severely hampered after the death of Muhammad Ali Jinnah in 1948. The Assembly’s lackluster approach to constitution-making was evident, with only 116 meetings held in the first seven years and attendance ranging from 37 to 56 members out of a total of 76. Many members held significant government positions, which limited their availability for constitution-making. The dual responsibilities of the Assembly — governing the state and drafting the constitution — diluted its focus, leading to minimal achievements during this period, including only the passing of the PRODA Act and the Objective Resolution.

F. Weak Political Culture

The deaths of Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan left a vacuum in leadership that undermined the democratic process. The subsequent political landscape was characterized by instability and the erosion of parliamentary democracy. Many political leaders, bureaucrats, and military officials prioritized personal agendas over collective goals, further fracturing the nation’s political culture. This environment of discord contributed to the delays in establishing a coherent constitutional framework.

G. Failure of the Muslim League

In most post-colonial contexts, the party that led the independence movement typically provided leadership during the tumultuous early years of the new nation. However, the Muslim League, which had successfully spearheaded the struggle for independence, struggled to transition into a viable political entity. It failed to hold any annual conventions in the nine years following independence, and infighting, along with perceptions of corruption, undermined its credibility. This decline hindered its ability to effectively lead the nation towards a stable constitutional framework.

H. Ascendency of Non-Political Forces

As political instability grew, the reliance on civil and military bureaucratic support increased, paving the way for non-political interventions. The Office of the Governor-General became a significant obstacle to the democratic process, as Governor’s Rule was imposed in several provinces, undermining the authority of elected officials. This shift allowed the vital task of constitution-making to be sidelined

Conclusion

The delays in constitution-making in Pakistan can be traced to a complex interplay of factors, including political distractions, religious and linguistic diversity, ineffective governance, and the rise of provincialism. These challenges underscore the difficulties faced in forging a national identity in a newly independent state and highlight the intricate process of establishing a constitutional framework capable of uniting a diverse populace. The legacy of these delays continues to impact Pakistan’s political landscape, revealing the challenges of governance and the importance of inclusive constitutional processes in nation-building.

Tailpiece

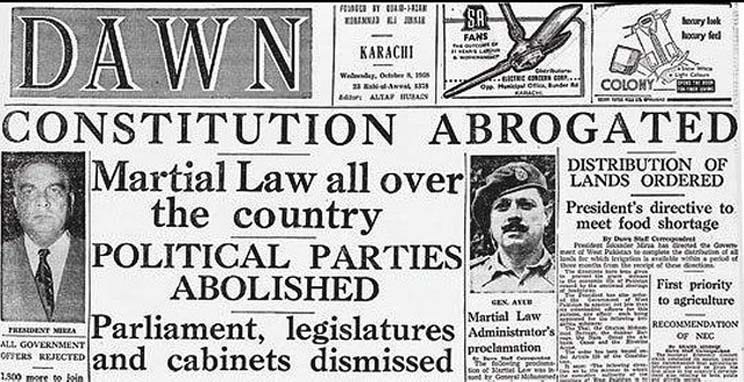

The 1956 Constitution was never practically implemented, as no elections were held. It didn’t fail, just became irrelevant because there was no one to implement it. It was eventually abrogated after about two years on October 7, 1958, when assemblies were dissolved and Martial Law was declared by President Iskander Mirza. Thus, all the efforts made to draft a consensus document were futile, cutting the very roots of the country as a united nation-state.

The 1956 Constitution, however flawed it might be, was a written agreement endorsed by the majority of the elected representatives who had taken part in the freedom struggle of the country, for their resolve to live together. Its abrogation nullified all the efforts made by the political elite of both wings to do so, cutting the very roots of the country as a united nation-state.

From the book “Pakistan Affairs: 25 Essays”, published by Amazon and available at

Request

Thank you very much for reading the article

If you liked it, kindly express your appreciation by clicking the clap icon below as many times as you like

Why not share it with your friends on social media? Knowledge is a common heritage of us all

And, kindly, do follow me as well as subscribe to my newsletter

You may like to read also

- Constitution-making in Pakistan: Causes of delay

2. Pakistan’s Water Crisis: Challenges & Response

3. Federalism in Pakistan: Challenges & Response

4. Pakistan Ideology: Sources & Contents

5. Causes of Breakup of Pakistan in 1971: Lessons Learnt

6. Pakistani Culture: Sources & Legacies

7. Pakistan-USA Relations: Challenges & Response

8. Public Policy Formulation in Pakistan: Main Features

From the Ebook “Pakistan Studies-20 Essays” by Shahid Hussain Raja, published by Amazon https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07JQ92JGY